Celebrating Muxes: The Resilient Third Gender of Mexican Zapotecs (CO)

For almost half a century, a largely obscure festival celebrating the Zapotec third gender has been taking place on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. Every November, around 10,000 visitors flock to the indigenous town of Juchitán De Zaragoza to partake in the three-day festivities. In Zapotec culture, a third gender known as muxe has been a part of this indigenous population since pre-colonial times. The festival’s name happens to be just as obscure and mysterious as the festival itself, Vela De Las Autenticas Intrépidas Buscadoras Del Peligro, which literally translates to Candle of the Authentic Intrepid Seekers of Danger.

The festival has been on my radar for a few years. I knew that it was in the Oaxacan region but had no idea where exactly and how one gets there. I reached out to my friend Diego who lives in Oaxaca with the task of finding out what he could about the festival. Diego is originally from Puebla; we became friends in New York City while working in the restaurant industry. A few years before the COVID pandemic, he moved to his hometown to pursue a full-time art internship, eventually making his way to Oaxaca and establishing himself as a full-time multimedia artist there. He also started a drag collective in Oaxaca and performed with his friends all over the city. Just a month after getting in contact with him regarding the festival, a muxe named Melissa, attended one of his drag shows and personally invited him to come to La Vela.

Upon my arrival in Oaxaca, I asked Diego if he would want to paint a backdrop for potential portrait sittings in Juchitán. On the night before our drive to the Isthmus, we had ourselves an abstract piece of art: a 12-by-4-foot piece of fabric in pink and reddish hues with a few green splashes. Diego’s unconscious homage to the Mexican flag.

Brief History

On the morning of November 18th, Diego and I were en route to Vela De Las Autenticas Intrépidas Buscadoras Del Peligro with our companions, Enrique and Ivan. Enrique works with Mexican Vogue, which, along with British Vogue, in a historic move, featured a muxe named Estrella Vasquez on their December 2019 cover. During the car ride, Enrique warned us that the community might not appreciate us barging in on them with a bunch of cameras and filming equipment and that we would have to be very conscious of how we cover the festival. Diego told me about this before, and at the time I felt pretty annoyed. His concern was our possible complicity in the festival’s gentrification. “I just don’t want to be a culture vulture,” he vented. “Diego, you are a Mexican drag queen, I am a Kazakhstan-born non-binary person. I think we deserve to be here and might fit in more than you think.” After all, Vogue, Vice and HBO have already covered La Vela in the previous years.

At the time, I hadn’t the slightest idea of the nuanced complexity that the muxe identity carries. As I found out later on, it could be almost impossible to truly understand it from a Westernized point of view.

Enrique’s friend Ivan who did the driving and who seemed to know most about the culture has been going to the festival for years and has deep connections with mayordomo and mayordoma (“butler” and ”housekeeper” respectively) who are largely responsible for organizing and paying for all of the major expenses connected with the celebrations. Mayordomos can spend upwards of 1 million pesos, which equates to more than $50,000. “It’s a great honor, but it is very expensive,” said Ivan.

Mayordomo (center) and mayordoma (to his right) during the Regada de Frutas or the Fruit Throwing Parade.

During our six hour drive from Oaxaca to Juchitàn, Ivan and Enrique explained that muxes have always been a part of the Zapotec culture, but have been falling out of grace within their society after the Spanish colonization of Mexico. Enrique offers, “The discrepancy happened when the Catholic Church arrived in Mexico during the Hispanic conquest. As you know the Catholic Church is very against all LGBT things, so the Church probably said, ‘Well, what’s happening here? You are accepting something that goes against the rules set up by God’. Probably this is where the break in idiosyncrasy occurred.”

Ivan filled us in on the man who has given muxes back their place in society: Oscar Cazorla. According to local tales, Oscar, who was originally from Juchitán, left his hometown for a period of time only to come back with a large sum of money. Upon his return, he opened a store and built a huge house, but quickly realized the grim reality of the day-to-day lives of muxes and gays in his hometown. He started taking them into his home and became known as their mother. “47 years ago, it wasn’t even a vela yet,” says Ivan, “It was more of a very small private party, not public at all. And over three decades ago, when Oscar returned and let other muxes into his home, the small private celebration began to open up. Oscar started normalizing being gay. Before this, the muxes were treated as bad as street dogs.” In 1976, Oscar's house established itself as a non-profit Civil Association called Las Autenticas Intrepidas Buscadoras Del Peligro, forcing government recognition under Mexico's Civil Code.

Muxes taking a break during Regada de Frutas.

Murders of muxes before the formation of the civil association were rampant, but these killings are still a problem even in current times. During the 2021 festival, when HBO was filming their documentary, “Muxes,” one group of muxes made it clear that there is still work that needs to be done. Enrique explains, ”They said, OK, this is a celebration and everybody wants to watch us on Netflix and other streaming platforms, but the reality is that there are still a lot of murders, and those cases are not followed through by the authorities because we are still considered as faggots of the society and we are still considered disposable. We are OK during the party, and we are OK in front of the camera, but the reality is totally different.” Ivan adds that in Juchitán one is safer because the community is bigger, and they take care of each other. Most of the muxe victims are in the towns around Juchitán because there are fewer protections. “What happens is muxes end up hooking up with local men and those men kill them because they don’t want society to find out or think that they are gay,” says Ivan.

“Gays are also still a very fragile community in Mexico,”

adds Enrique, “Last week a gay couple was walking on a fancy Masaryk street in Mexico City, similar to Park Avenue. There were some guys eating tacos in a street stall and they saw the couple sharing a kiss and they basically acted like real animals and beat them up really badly. In the end, you can see how Mexico is still a very traditional place with a lot of deep-rooted homophobia.”

Zapotec youth dances in the mayrdomo and mayordoma costumes.

Who Are Muxes?

When it comes to muxe classifications, it tends to get really muddy, at least when you look at it from the Western way of understanding genders and pronouns. There are no genders in Zapotec language, so there doesn’t seem to be a set way to gender a muxe in another language. Some refer to them as “he,” and some refer to them as “she,” and they both seem to be acceptable. But when I thought I had it all figured out, I was wrong. At first, I thought that muxes were trans, but I was corrected by Klever, a muxe who lives in a neighboring town of Unión Hidalgo:

“Muxes are not trans, we are muxes.”

So does that mean that muxes could claim a letter of their own in the LGBTQIA+ acronym because of their cultural specificity? No one can completely understand what it is like to be a muxe unless you are born into the Zapotec culture. It’s not an identity you can simply take on one day. Natural History Museum of LA County explains it, “Within a Western and Christian ideological framework, individuals who identify as a third gender are often thought of as part of the LGBTQ community. This classification actually distorts the concept of a third gender and reflects a culture that historically recognizes only two genders based on sex assigned at birth–male or female–and anyone acting outside of the cultural norms for their sex may be classified as homosexual, gender queer, or transgender, among other classifications. In societies that recognize a third gender, the gender classification is not based on sexual identity, but rather on gender identity and spirituality. Individuals who identify with a cultural third gender are, in fact, acting within their gender/sex norm.”

There are different types of muxes and one of the star’s of HBO’s “Muxes,” Elvis Guerra makes it plain in the interview for Cultural Survival: “Muxe is a gender identity that has to do with men who are biologically born male and that over time adopt another gender different from their birth. Muxes adopt exclusive roles of women; they are people who have sexual affinity with the same sex. Unlike gays, the muxe community have very particular characteristics that have a lot to do with their sexuality in the way they exercise it. They may or may not be dressed as women. There is a historical rule that muxes should be passive in a sexual relationship. There is no sexual or affective relationship between two muxes.

For the Zapotecs there are four genders: woman, man, lesbian, and muxe. There are no bisexuals, transsexuals, intersexuals, or asexuals; rather, everything else is defined from the muxes.

There are the muxe nguiu: muxes that are men who do not dress as women, who sometimes decide to even marry a woman and have children, but perform socially feminine functions and that society identifies as a muxe nguiu (“man’s”) body. There are muxes gunaas, which are those that are assumed as women, who believe that their body should be that of a woman, who live and adopt the dress of a Juchitecan woman; the closest thing would be the trans. There are also the lesbian muxes who break the aforementioned rules because they can relate to another muxe, and have a love, dating, and sexual life. It is also called lesbian because it is the concept of two women together. Then comes a subcategory that has to do with women dressed as women who are active in a sexual relationship and are known as ramoneras. Ramoneras take the roles of men in bed. The name has a poetic origin; as it was a closed practice, muxes could not be active, and they were the ones that broke the rule. The first man who turned was called Ramón. But since this cannot be named, the word Ramón was used as a form of euphemism, to say ‘there goes another one that turns around.’ These are the peculiarities that have to do with the Zapotec culture and that make it different from Western culture.”

Muxe gunaa at Regada de Frutas.

The Run Of Show

This is what the weekend of the La Vela typically looks like:

Day 1– Regada De Frutas, or the Fruit Throwing Parade, where muxes march through the streets of the town showering people with fruits and household products. This is also where people see the first grand presentation of the queen-to-be.

Day 2– a religious mass for muxes followed by the main event, La Vela.

Day 3– Lavada de Olla, a small traditional vela that closes out the festivities.

Regada De Frutas

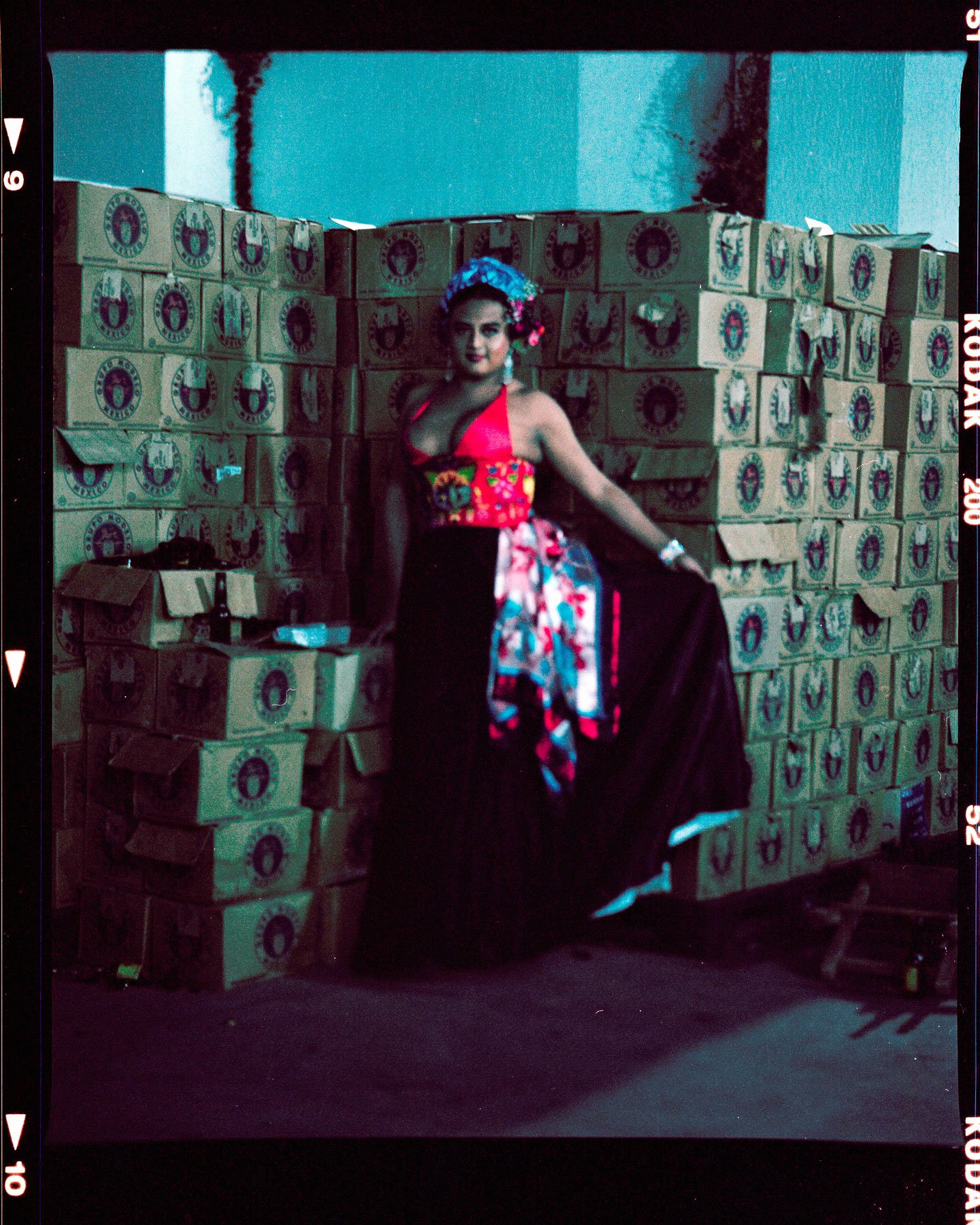

Hundreds of people lined the streets of Juchitán, hands outstretched in order to catch the fruit or household items like lightweight plastic plates thrown by the muxes from the passing floats. At the head of the procession, a few carts pulled by oxen were carrying young girls dressed in their best trajes–a traditional two-piece skirt and huipil (tunic) suit embroidered with meticulous flower designs by the hands of local artisans. It takes an incredible amount of work to embroider one traje. La.

Of course, the main event of the Regada is seeing the current year’s Queen-to-be. It was queen-to-be Melissa who invited Diego to Vela De Las Autenticas Intrépidas Buscadoras Del Peligro. Of course, she had the tallest, the most lavish float. “It’s all about the money when you are crowned as the Queen. You have to be able to afford it,” said Enrique. Two years ago the crowned Queen La Verdugo shared that she spent around 150,000 pesos on her coronation, nearly $8,000. Felina, who co-founded the association along with Oscar Cazorla, and who is another star of HBO’s “Muxes,” expressed this in the documentary: “La Vela has grown immensely, so the queen needs a big investment. The present queen wants to be better than the previous one. If you want to do that, you need to invest in production, and that’s a lot of money. Your dances, your costumes, your parade float, your costume for the mass, your stall, it’s a lot of money. That is, if you want to have an impact. You can’t just come and say, ‘Look, I’m beautiful, I’m the Queen.’ They’ll eat you alive. In the end, they win, we don’t. I’ll put up the stage, and then you decide what to do. Either you make it big or you flop. They all want to make it.”

The Mass

On the second day muxes held a morning mass at Esquipulas Church. It was a big scene with dozens of onlookers, many of whom were obvious visitors just like us. There were one or two muxes pulled to the side by a swarm of photographers–I stepped behind the commotion and tried to capture the tiny chaos that ensued over them.

In a short while, a long muxe procession exited the church and headed out into the streets. By the time I finished swapping out a roll of film in my camera, the procession was nowhere to be seen. Everyone was heading to the house of the mayordomo to enjoy drinks and food before getting ready for the main event of the festival– La Vela.

We were loosely invited to come to the house of the mayordomo by a local guy we met at the church named Braulio, but we were never really given an exact address to go to. Diego and I waited for an hour under the scorching sun hoping to get the directions to the house. We never heard back from Braulio, but we were confident that everyone in the town would know where the lunch break was taking place. After a few motorcars refused to take us without the exact address, we realized that we’d been naturally filtered out by the community. We were just visitors and to be invited to the home of a mayordomo, you have to be family.

La Vela

By buying a 24-count case of beer from one of the sellers right at La Vela’s entrance, you gain access to the event. You can bring the beer to any stall hosted by a muxe and then you must eat and drink until you cannot anymore. “You can’t refuse anything they give you,” Ivan warned us, “they can take great offense to that.” Typically, only muxes that assume women’s roles set up a stall, each seating a few hundred guests. The doors to La Vela open at 5 PM and the partying is expected to go on until sunrise. It's a tradition to stay awake all night; this is how their ancestors thanked the saints.

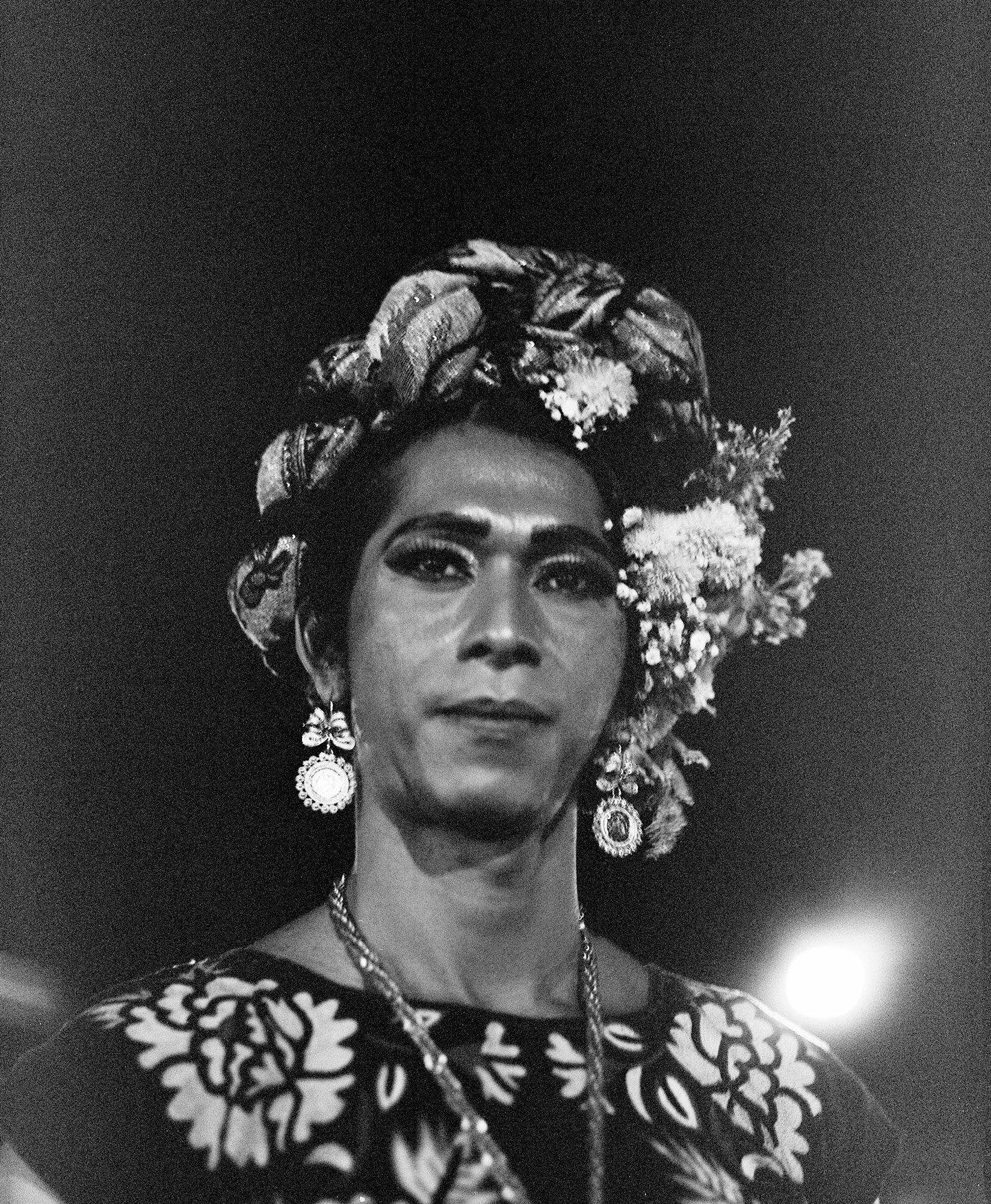

At La Vela, Tehuana women and muxes are dressed in their best trajes, with real flowers and ribbons woven into their hair. Traditionally, it is known that a flower transmits a delicate intention, attracts the eyes of others, and represents the happiness and nature of a woman. In Juchitán, if women wear flowers on the left side of their head, they are señoritas (unmarried women), and if they wear them on the right side, they are señoras (married women). If a woman is widowed, she would wear her flowers on the right side of her head, but the flowers would be white or black, not ones with color.

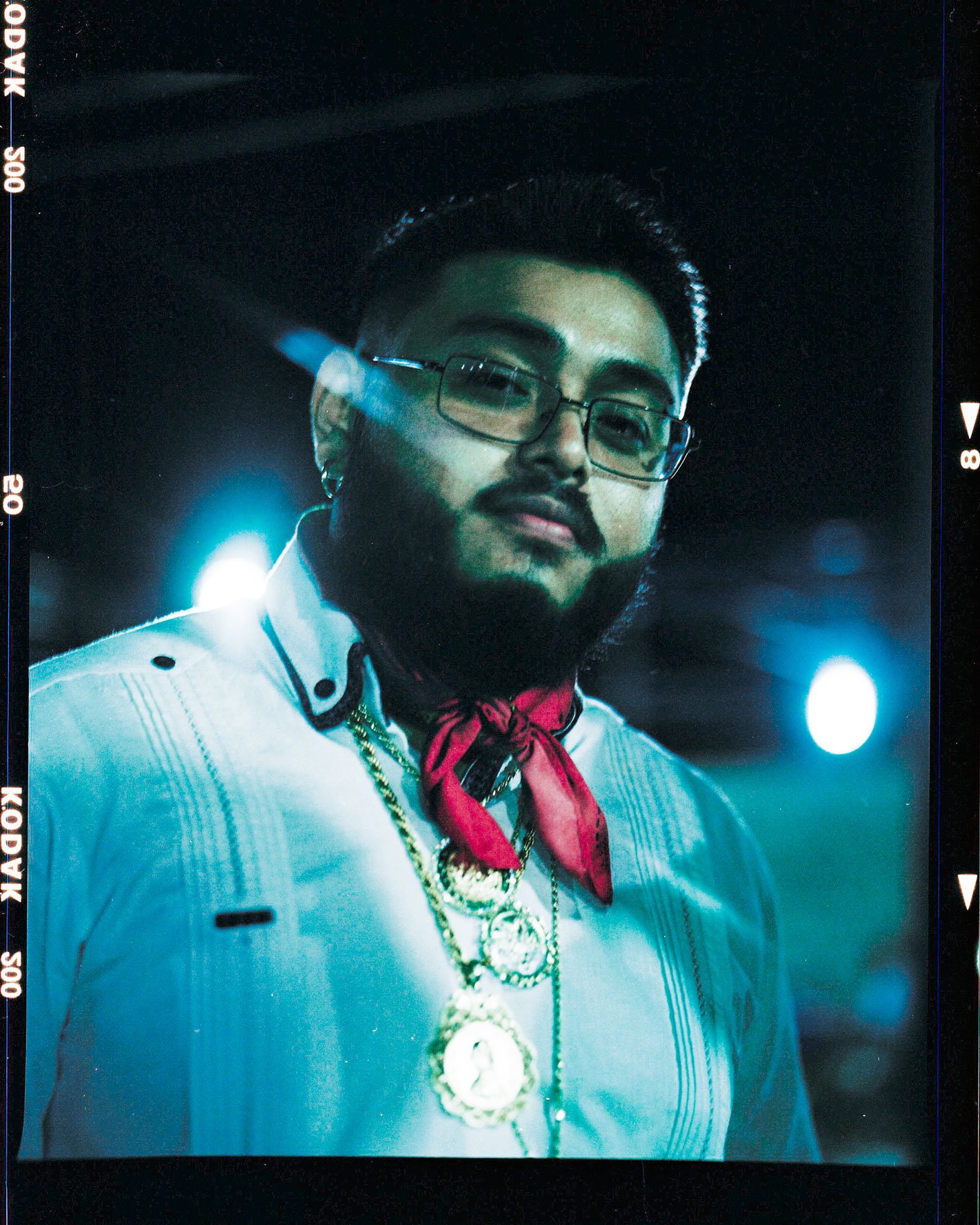

The men traditionally wear light-colored shirts made of cotton or linen called guayaberas. Guayaberas typically have pleated stripes on the front and sometimes are embroidered with flowers. The rest of the outfit consists of black dress pants, leather huaraches (sandals), and a wide-brimmed hat or a colorful bandana around the neck.

Diego AKA Guadalupe Reyes in the middle, with Braulio on the left and Enrique on the right.

Before coming to the event Diego was very worried about wearing the wrong thing. Enrique and Ivan told us that gay and straight men are expected to wear traditional attire. After a few conversations about it, I convinced Diego to be himself and dress however he’d like. I was going to do that myself as well. Diego decided to go out in drag since Melissa invited him to the festival while he was in drag in the first place. While Diego was putting on makeup, I decided to put on some light makeup too; I let my hair down and dressed in low-rise jeans and a cropped white button-up shirt, exposing my stomach and my lower back. I don’t know how you’d characterize my look in Zapotec, but whatever it was, it caused quite a splash. It was a hit with muxes, gay men, cis and trans women. One of the biggest fears Diego and I shared was that we weren’t going to be accepted and we would be treated as intruders by this remarkable community. But the amount of attention, smiles and care we received from the locals was overwhelming. I’ve never really felt as uplifted, seen, or accepted as I was feeling at La Vela.

At some point in the night, I passed a young woman whom I recognized from the Fruit Throwing Parade. She was one of the girls who spearheaded the march on carts pulled by oxen. She gloriously wore a white ruffled headdress called huipil grande that the Tehuana women wear on special occasions. There was an air of pride in her stature and warm openness in her smile. We both stopped in our tracks like we already knew each other and shared a hug, our connection was instant. In my best Spanish I told her that my name was Alexey, and she said that her name was Amanda. She introduced me to her brother Leyver, and I quickly fished out Diego from the crowd. “Hey, I want you to meet somebody special,” I told him, “this is Amanda and this is her brother, Leyver.” I knew they would click right away as well. Amanda’s eyes lit up when she saw Diego in drag. I asked him to tell the brother-sister duo that when I saw Amanda in the parade, I fell in love with her and the white headdress she was wearing. Leyver spoke to me through Diego, “I would like to gift [the headdress] to you if you liked it so much. I made it myself.” I was confused. Why is he being so nice? “I want you to have a good memory of this place and your experience here,” replied Leyver. I was blown away. I kept looking over at Diego in disbelief. “It’s okay Alexey, just accept it, people are genuinely nice here.”

When asked why young women were at the head of the muxes procession, Amanda replied: “Because the mayordomo wanted to include us to show that we are all the same, in a way our generation was paving the way for muxes.”

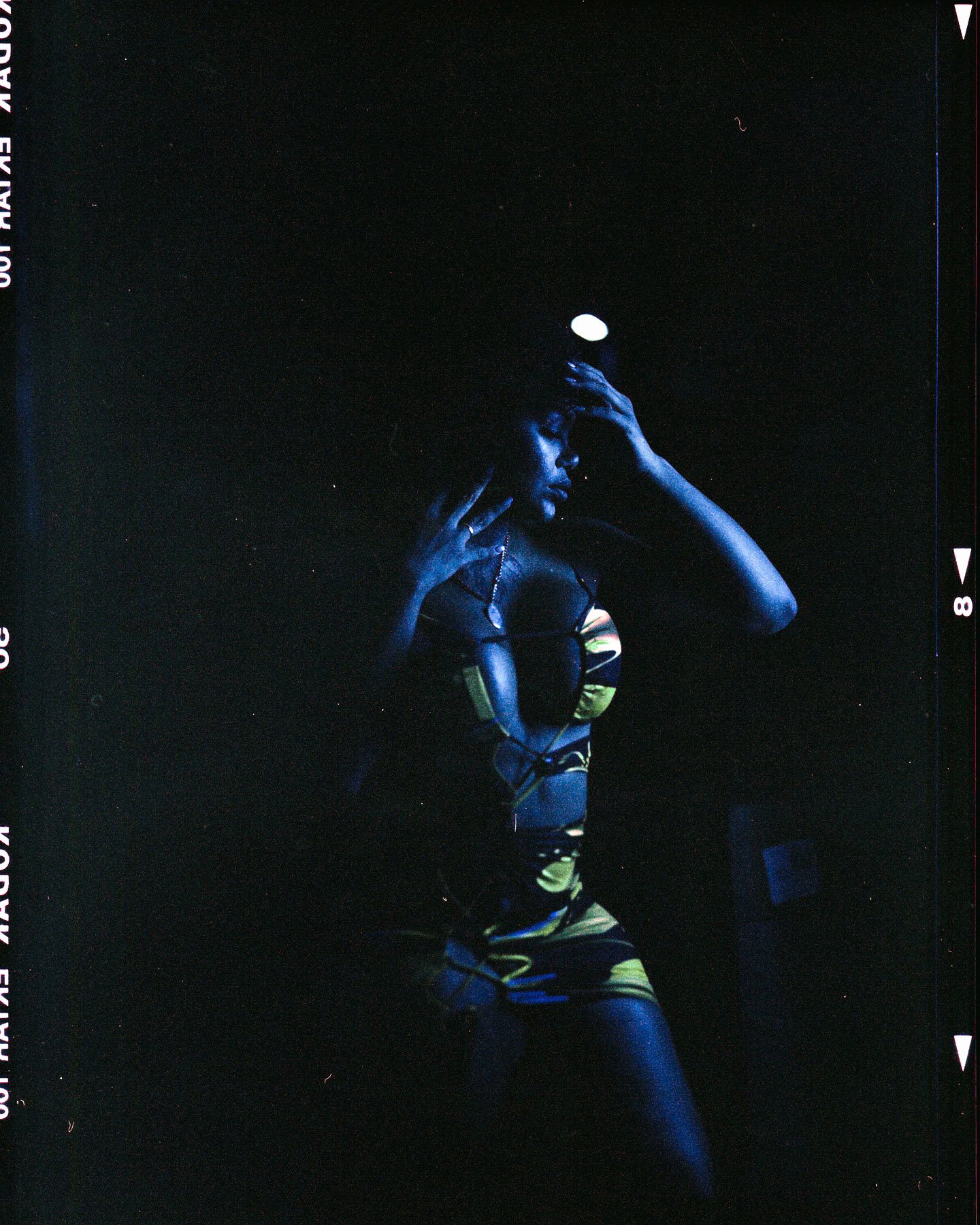

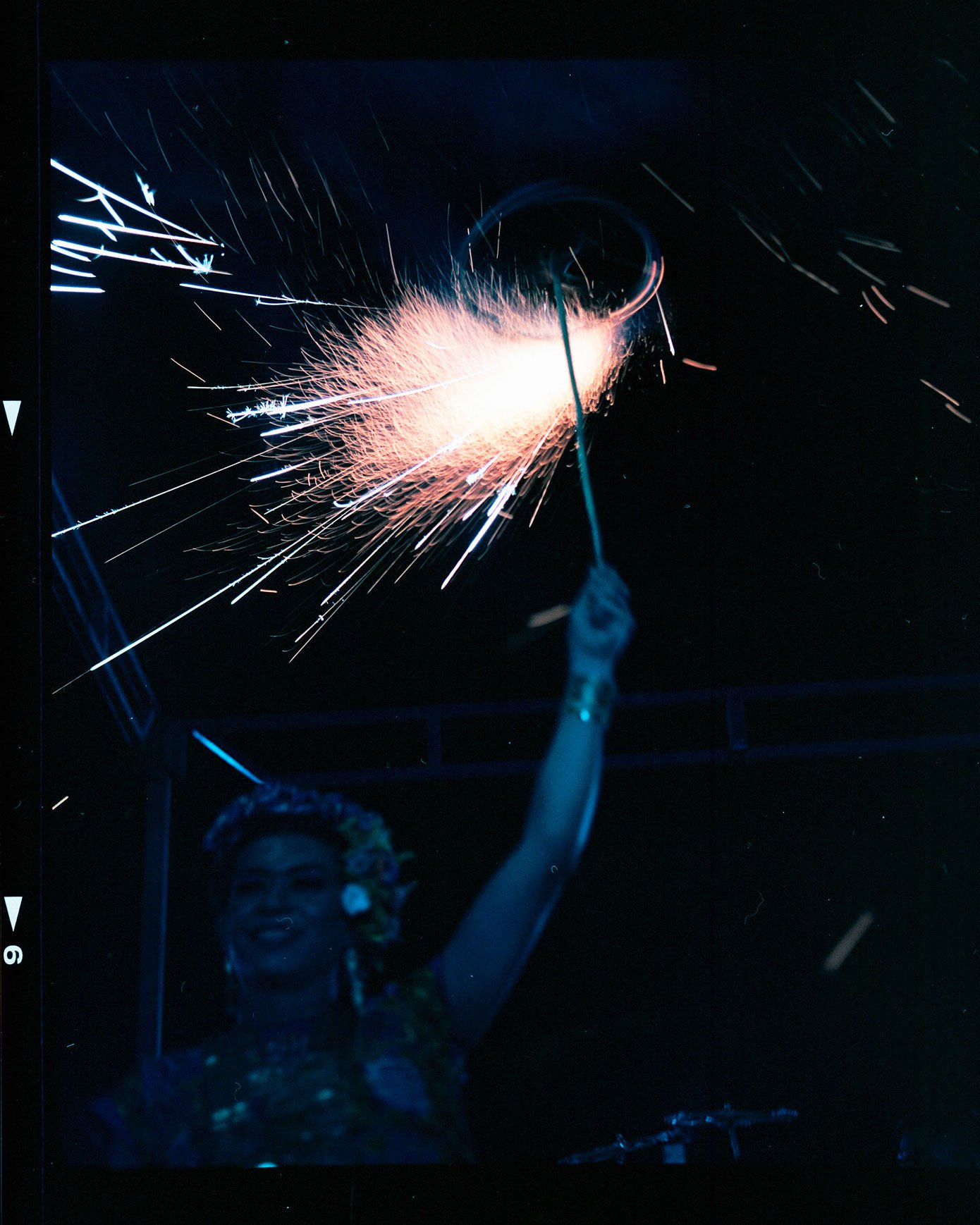

The night continued with dancing and the grand appearance by Queen Melissa. She stirred a big commotion with about a dozen dancers dressed in colorful cloth strips, large sombreros, and animal fur face masks known as titliches. She first appeared wearing a trans and rainbow flag dress, then later in the night changed into an elaborate pink gown with a feather contraption that kept on shifting to the side because of its weight and the strong wind. The coronation proceeded and the rest was a blur.

Last Day Of La Vela

The next afternoon Diego and I met Amanda and Leyver in one of the city’s squares. We asked them at La Vela if Amanda would like to have her portraits taken in one of the city’s squares. Amanda showed up in a beautiful two-piece traje embroidered with flowers. We’d set up a backdrop painted by Diego back in Oaxaca. Amanda was facing it for a few minutes silently. “This is beautiful,” she turned to Diego.

Halfway through the shoot, Leyver took out the glorious huipil grande, also known as a resplandor, and showed the proper way of wearing it on Amanda. “Alright, now spread out the resplandor as much as possible,” I encouraged Amanda, “face the sun, and give me a big smile. Beautiful!

Later that evening we headed over to Lavada de Olla that would finish off the three-day celebration. It was much smaller, with less extravagant costumes, fewer attendees, and less decorations. “This is a more traditional vela, most of the visitors left after last night’s party,” said Ivan, “but look at these muxes. They’ve built something for themselves here. They have real power and respect in this community, look at all the business and money they bring into this city. It’s incredible to witness.”

Special thanks to Diego, Ivan, and Enrique for making this trip happen, working as guides and translators, and for explaining the culture. This article took an entire year to be crafted and it’s finally seeing the light of day because of Chase Isbell’s diligent and brilliant work as an editor. We’ve gone through countless rounds and changes and I couldn’t have done it without her.